I’m sure there’s a joke to be had about how I like my male horses – tall, dark and handsome, yes, but also – gelded? troubled? – but what I do know is that the geldings I have picked as riding horses tend to have a lot in common. The three I have chosen have been bay with strong black points, similar height, and with no interest in the job they were trained to do before I met them.

Soldier was a thoroughbred trained to foxhunt. I got him as a lease-to-sell project, with the intent of training him as an event horse. As it turned out, a horse who will run and jump with a group of other horses does not necessarily have any interest in jumping when he is alone on a cross country course, and a horse who has only ever seen natural fences on the hunt course may not have any idea what to do with painted jumps in an arena. His approach to a stadium jumping course went something like this: gallop towards the first fence, screech to a halt, take off from all four feet at once, land on all four feet on the other side, bolt to the next fence and repeat. After it became clear he would never be an eventer at even the lowest level (Super Chicken, they call it locally, or Ever Green), his owner sent him back out on a foxhunt with an interested buyer who Soldier promptly dumped and nearly put in the hospital. He eventually found his way to a great home with a woman who wanted mostly to do dressage and trail ride.

Wy came along about 5 years after Soldier. His full name was Wy’East, the native name of Mount Hood, the highest peak in Oregon where his breeder was from. He had been bred and trained to be a dressage horse (his breeder had dreams of him taking her to the Olympics) but was deemed neither sound nor sane enough for that job. That put him squarely in my equine specialty of what a friend once dubbed “the lame and the insane.” His first owner was my dressage instructor at the time she had him up for sale. When I rode him for the first time in a lesson with her I wound up on the ground pretty quickly, as his riders often did. I don’t remember landing, but I do remember getting up and saying “You son of a bitch, get back here” as I went to get him from the other side of the indoor arena. His owner, used to people sitting on the ground and crying after coming off him, agreed to sell him to me on a payment plan.

I had no designs on Wy as a dressage horse, and I let him show me what he was interested in, which was mostly trail riding, though he also loved jumping tiny fences as if they were Puissance walls. With the pressure off he got a lot saner, but he didn’t get any sounder, and I still had vague ideas at that time about having a horse I could compete in some discipline. I decided that he might be happier in a home where all the person wanted to do was trail ride, so I sold him to a nice man who wanted just that.

Several years after I sold Wy, and several farms after the last one where he had lived with us, we were house hunting again, looking for a place for us and our three mares. We were thinking about a house that had the right amount of land, but the land was mostly wooded. While we investigated how much it would cost to turn woods into pasture, we looked at barns where we might keep the horses in the interim.

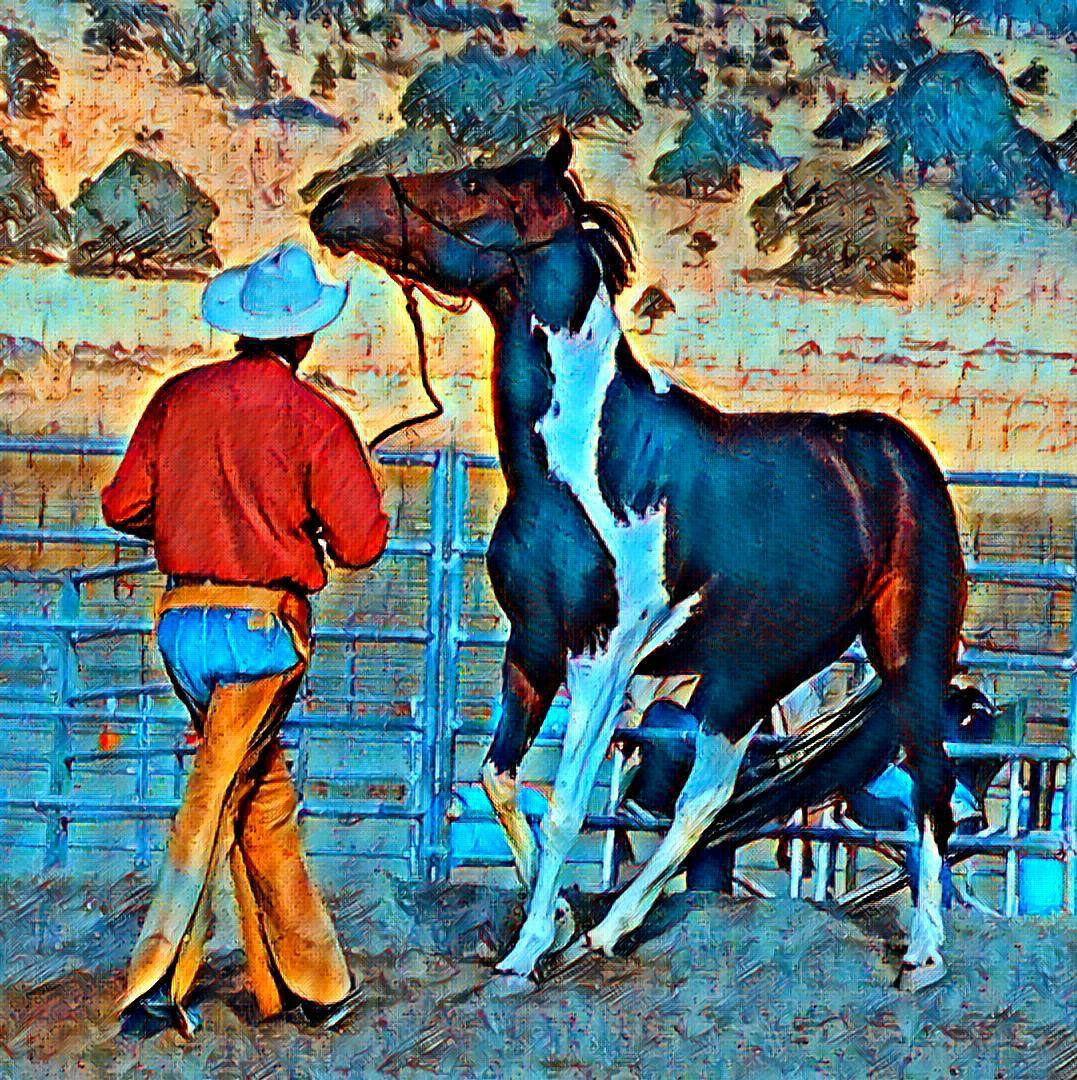

There was a good sized boarding farm close to the woodland house. We arranged to visit, and the owner – something of a cowboy in the middle of hunter/jumper, eventer, and foxhunter territory – showed us around while we told him about our mares. I was explaining about my slutty thoroughbred mare Trappe, and telling stories on her mare-in-heat behavior, when I said “Of course, that was when we still had Wy.” The cowboy said “You had a horse named Wy? We have a horse here named Wy.” I said “Is it ‘Y’ as in the letter Y, or ‘Why’ as in ‘Why Did I Buy This Horse?'” He said he didn’t know; the owner just called him Wy, or sometimes Beast. Even though Wy’s most common nickname when I had him was Wy Beast, I still didn’t make the connection. “He’s a big, bay Hanoverian gelding,” said the cowboy as he pointed behind me. This finally sunk in, and I turned around and saw my horse looking at me over the fence of his paddock. I ran over to him and he buried his big head in my chest.

Wy had come to this farm through two different owners after he got sick while with the guy I sold him to. The diagnosis by the time I saw him was possibly EPM (equine protozoal myeloencephalitis), but no one was really sure. Some kind of degenerative neurological condition, definitely. He was not rideable, and his owner was trying to decide what to do next. I wasn’t sure what to do next either. I did nothing for about two weeks, and then one Sunday I woke up and said to Rose, “I had a dream about Wy last night and he told me to come get him. I want to go back to the farm to see him.” When we got to the farm I told the cowboy about my dream, and he looked at me like I was a little nuts, which I had expected. I said “I know it sounds weird” and he interrupted me and said “No, I don’t think it’s weird at all – it’s just that his owner just had the vet out yesterday and he said there’s nothing else they can do and she was asking if I knew how to reach you to talk about having you take him back.”

Wy came home to us and the three mares he had lived with before, though at a different farm. When we first put him out in the field with them, he spent a couple of days with a look on his face like “I had the weirdest dream – but here we all are together so I guess it really was a dream.” The mares – especially the slutty thoroughbred – were thrilled to have him back. We didn’t buy the woodland house, but we did buy the house where we live now. By that time we had acquired one more filly and we also had a foal on the way. They all lived at our vet’s farm for a few months while we put in fence and a barn here, and then they came home.

Less than two months after we brought the horses home, Wy had gone downhill enough that we had to put him down. He couldn’t reliably stand up without his knees buckling, and he walked like an old drunk man. With Trappe standing close at all times and trying to prop him up, I was worried that I would come home to find them both on the ground with her squashed beneath him. Our vet, who hadn’t seen Wy since he came home to us, took one look and said “You know you don’t have a choice about this, right?” which, true or not, was what I needed to hear. We buried Wy near the barn, and everyone that drives onto our property drives by his grave. A year after we buried him, an acorn sprouted in the middle of his grave, and that oak tree is now about 30 feet tall.

Wy left a lot of legacies. One of them is one of our family mantras: “Don’t pick up the reins.” It took me until the second time I came off of him to realize how he got people off so consistently. He would wait until his rider had a good hold of the reins, and then he would duck his giant head down between his knees and pull the rider off balance, and then he’d throw in a buck with a twist and off the rider would pop. The thing was, he always had something a little off in his back and hind end, and his buck really was not that athletic. I discovered that if, when he put his head down, I let go of the reins, he could buck all he wanted and it would not unseat me. It was that rein yank that created the problem. It became something Rose and I would say any time anyone verbally tried to knock us off balance in an argument – don’t pick up the reins and you won’t find yourself getting into a fight.

Finn is a legacy of Wy’s. I’m sure it’s no coincidence how much they look alike, or that Finn was another horse that someone tried to turn in to a dressage horse when he neither understood what was being asked of him nor was he interested in it. I don’t know that I would have brought Finn home if I hadn’t known Wy, and I don’t think I would have listened to him as much as I have when he tells me what he does and does not want to do and what he can and can’t handle. I still needed some reminders, like the first time I asked Finn to trot and he said “I can’t” and I mistook that for “I need some encouragement” rather than “I really can’t do that right now.” I said “Come on, you can do it!” and then I was up in the air looking down at his back, and then I was on the ground with him looking down at me with a look that said “I told you I can’t and I really meant it.” I got up, dropped my pants to get the sand out of my underwear, pulled myself together, and got back on with a different attitude. Finn is the Truth Serum Horse in his own right, but I know how to listen to him because of Wy.

Wy’s biggest legacy for me is to pay attention and to trust my gut. I don’t think it’s out of the realm of possibility that we went to look at one house so that we’d meet the realtor who took us to see another house that was the reason we went to look at the barn where I found the horse and was able to bring him home. Life doesn’t always run in straight lines, but I find that if I just keep moving forward – and if I don’t pick up the reins to try to control something I have no business trying to control in the first place – I end up where I need to be.