I have a collection of partially written blog posts that I may or may not get around to finishing. It seems that instead of taking notes these days I sometimes start a blog – maybe with a photo, or a title, or a sentence, or a paragraph, on the theory that I will remember later what I wanted to say. There’s one that only has a title – Layers – which I hope was going to be about more than cake, but maybe cake is enough. There’s one called Cat Dog which has two photos of my first dog when she assigned herself to be the parent of the then brand new kitten, Pigwidgeon, but the only sentence in it is about my mother, who was far more cat than dog. Maybe it was going to be about being a dog child raised by a cat mom, though for the first forty or so years of my life I would have said I was a cat person. There’s one called Eggs, which begins with this paragraph: “I’ve been thinking about eggs. Actually I’ve been eating a lot of eggs, and noticing that every time I crack open an egg, I think of my mother. Not in a symbolic, mother-daughter, mysteries of the feminine kind of way, either. In particular, I think of cracking, and then beating, what felt like thousands of eggs, during the Meringue Years.” A few sentences later, it ends in the middle of a word (“Quite possibl” is where I stopped, having used up my day’s quota of not only words but letters, I guess).

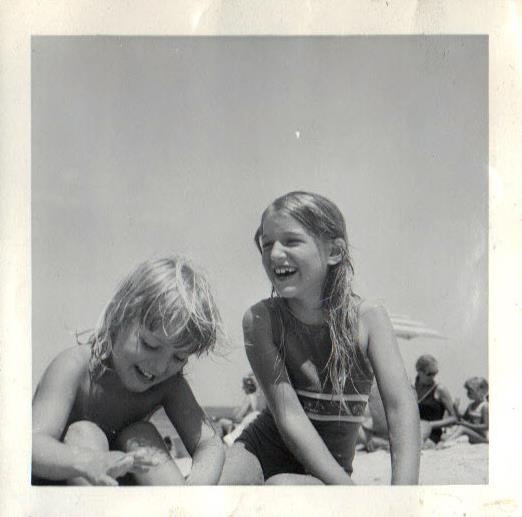

Many of my partial posts started with something from my childhood, and those shards of childhood memory are on my mind a lot lately, as are my parents and my two older sisters. I have very few memories of events of any significance from before I was ten, but I can perfectly describe the dented stock pot we used to make both pasta and fudge (not at the same time). I can tell you about the time when the crabs (aka dinner) escaped under the kitchen stove, though the fact of it is all I remember, and not the method of escape or rescue, if “rescue” is a word that can apply when the rescued end up in a pot of boiling water. I can tell you general facts about each person. For example, my father used olive oil as tanning lotion, and we used to have to keep him out of the kitchen while making spaghetti sauce so he wouldn’t sneak in and add so much hot pepper that no one else would be able to eat it, and he often made oblique requests (“A beer would be nice”), and it was next to impossible to tell when he was joking.

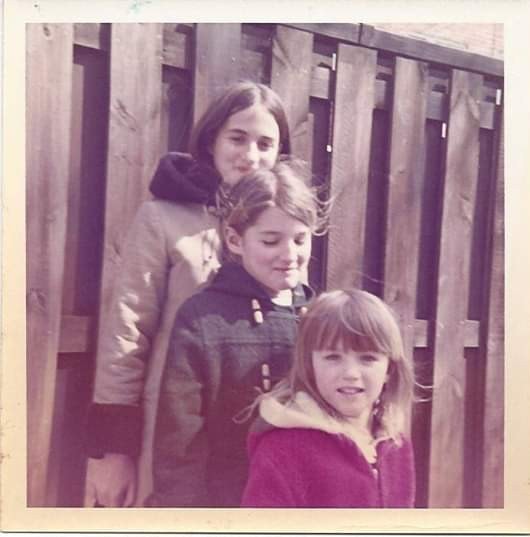

As the youngest of three sisters spanning a seven year age difference, I probably have the vaguest memories of the times we were all together. My oldest sister had the most and the clearest memories, partly by virtue of being the oldest, but mostly because she had perfect recall of all names, dates, events, and relationships, plus every fact she ever read or learned. She would always be the person I would ask for birthdates, who was married to whom, how we were related to someone, or when a particular vacation or trip to the circus took place. I’m always interested in the things family members remember differently, or don’t remember at all. She seemed to remember everything, and I don’t think any of us would ever have questioned her. I have a collection of photo albums in my basement from my aunt and my grandmother, and no one to ask who is in them.

My maternal grandfather died before I was born, and my maternal grandmother when I was in college. My paternal grandfather was not a part of my father’s life, and I was never close to his mother and stepfather, both of whom also died when I was in college or soon after. My uncle died when I was in high school, my mother when I was in my late 30s, and my father and my aunt died within two weeks of each other seven years after that. One day my sisters and I and our three cousins were the kids, and the next day we were the older generation. It’s the normal order of things, but it happened all at once and before any of us had really thought to prepare for that particular fact. I think it’s safe to say the last thing I expected then was that one of us – my oldest sister – would die five years later. I’m still not sure I believe it.

I spoke to my sister – I still want to specify which one, though it’s just the two of us now – yesterday. I used to envy how close my mother and my aunt were as adults. For a lot of years my sisters and I got secondhand information about each other through our parents, which works kind of like social media where you can keep up with someone’s life without actually making an effort to communicate with them. There’s a lot to a sister relationship: the years we lived in the same house, the years we fought, the years we were best friends, the years we didn’t speak, the places our lives connect and the places they don’t at all, the things we know about each other that no one else knows, and the things we will never know about each other. My mother and my aunt got closer after my uncle’s death, and still more after my grandmother’s death. It never really occurred to me that their closeness might in part have been because they were all the family each other had left, the only two people still there to hold on to – or argue about – the memories.